Japanese contemporary theatre has failed.

Consider the furore that greeted Caryl Churchill’s Seven Jewish Children earlier this year in London. Churchill is probably the most innovative playwright in the nation; she is certainly the best British female dramatist ever and, along with Stoppard, arguably the greatest living British playwright. Like Beckett’s did as he got older, her work has also grown increasingly minimalist and oblique, though it is refreshing to see her now returning to politics. And what politics. She choose to turn her always pointed eye on Israel and Gaza. Churchill publically advocates the Palestinian cause and the play has been (perhaps predictably) vociferously attacked by many as anti-Semitic. The play is typically bold in form: a brief ten minutes, written in haunting non-rhyming verse of multiple parents’ messages to their children discussing what to tell them about Israel – and what to keep secret.

There have been a plethora of plays in the UK dealing with the Gulf conflict (most notably Black Watch by Gregory Burke and Stuff Happens by David Hare) and other contemporary issues (e.g. the Deepcut Barracks deaths). Churchill’s is not even the first high-profile drama about Israel and the Middle East. We have also had My Name is Rachel Corrie at the Royal Court and the West End. Some of these have explored the documentary drama form, though it is more their content that has attracted attention. In the Nineties with the rise of In-Yer-Face Theatre plays moved away from agitprop and socialist agendas, focusing on malaise, the post modern urban condition. Is political theatre back?

Caryl Churchill's 'Seven Jewish Children'

German-language theatre has been quick to react to media storms such as that surrounding Austrian Josef Fritzel, the father who kept his daughter in his basement for twenty-four years and raped her. A play (Pension F by Hubsi Kramar) produced during his trial satirized the TV coverage and demonization of the man. On top of producing international playwrights like Marius von Meyenburg, Dea Loher and Peter Handke, German theatre responds often immediately to the shifts of the zeitgeist.

There is a distinction between relevant, fresh theatre expression and knee-jerk reactions, to jumping on the bandwagon. However, where are the Japanese plays about Article 9 and its reform? Where are the Japanese plays about the poverty that continues to rise? (The poverty that has been here since the Bubble but now worryingly seems to be affecting younger and younger people – creating a whole lost generation of twenty-somethings who live in Internet cafes.)

There has been a lot in the mass media about both these things. There have been lots of demos (though not necessarily well-attended). There are dozens and dozens of new non-fiction books; journalists are fascinated by the topics, it makes good copy. There has also been quite a bit of art about the Constitution issues (in particular Shinya Watanabe’s touring exhibition “Into the Atomic Sunshine”). But where are the plays? As far as I am aware, no one has tried to tackle them. (Come to think, not just stage plays – but where are the films and novels? Of course TV drama is a dead loss here and could never dream of addressing such serious subjects.)

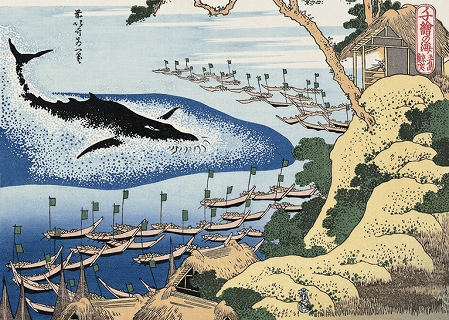

Have there been any plays in Japan about whaling?

The plays of chelfitsch and Potudo-ru feel very contemporary; they seem to be investigating the lifestyle of the urban young today. But they are examples of In-Yer-Face Theatre and their presence is not enough. (Further, I have yet to see a Japanese play that explores the violence of In-Yer-Face Theatre a la Sarah Kane, Ridley and Nielson.) The most important issues today in Japan (and the world) are being ignored: the plight of the Ainu; whaling; the death penalty; the new jury system; political corruption. Here’s a cracking subject matter: Japanese politics and media is suffused with anti-Semitism (and yet, contradictorily, there are also the Schindler-esque tales of Chiune Sugihara and Kiichiro Higuchi). Dare I say it but where is the Japanese David Hare?

Is there a Japanese David Hare out there?

Churchill has also taken the unusual step of having the whole script of Seven Jewish Children (albeit only eight pages in total) available as a PDF, and allowing productions to be staged gratis as long as no charge is made for admission and a collection is made in aid of Gaza. (Sadly the controversial nature of the piece has prevented some productions from taking place.) Admittedly, Churchill is a successful playwright with at least some modest financial reward from her previous work (Top Girls, Cloud Nine, Serious Money), and it no doubt means she can do this kind of thing. (There is even a version available for free viewing on the Guardian’s website.) But would a Japanese writer be willing to do it? Their confinement in the gekidan system means they have very little practical security and could never afford, literally (and literarily) to take this kind of step. But the first step to overcoming those practical difficulties is to have the creative impulse to tackle the subject matter in the first place.

I followed the link from your comment in Guardian Blog (there I used a name, Ludus).

I can see very little, if any, political impulse in the current Japanese theatre, which seems to be taken over entirely by commercialism, Ninagawa most clearly illustrating the change. But then, if I look at the Japanese public in general, people are not interested in politics; the theatre only reflects the current state of political inertia. I sometimes think that it is just the nature of Japanese people to be like this, but then it was quite different about 30 years ago: the public and the theatre pulsated with current political issues. The important issues you cite above, except perhaps the jury system, do not seem to interest Japanese public generally; they are issues which many western people are interested in, regarding Japan. Issues which other countries think we should pay attention to are not those which most Japanese people are concerned right now, such as aging of society, the future of pension scheme, problems with N. Korea, bullying in school, poverty, and, most of all, recession. Insular, isn’t it?

On the other hand, the political awareness and fierce independence which, for instance, the National Theatre boasts of in UK are internationally an exception rather than a norm, I would think, and which the British can be duly proud of.

LikeLike

Hi Yoshi/Ludus,

Thanks for your comment.

Sorry about my long, rambling comment on the Guardian Blog. I didn’t mean to seem to be attacking you or disagreeing with you! It was more all the critics claiming that they didn’t like the play because it was too Japanese for them, that something was ‘lost in translation’. It’s too easy an excuse. (Similarly, the response to Shunkin made me angry.) (And yes, there have been some productions of Madame de Sade, such as at the New National Theatre a few years ago.)

You made some excellent points on the Guardian Blog about audience responses to Kabuki (what a great comparison with Sumo), and the contrast with Noh in terms of the audience demographic is also very valid. To an extent these divisions probably survive till today; I’ve never seen audience data for Kabuki vs. Noh but no doubt the former is much more varied and popularist.

The contemporary gekidan here get a young audience but it always feel very clique-ish, like being a member of a club. In this respect it is also ‘elitist’, or at least subcultural. For other theatre practitioners, such as Mishima, I am still not convinced if he was truly concerned about pleasing an audience. Certainly he wanted popularity and success, but he also possibly wasn’t interested in ‘giving’ something to the audience (like Kabuki) does. What do you think? (To meander, this is something I’ve always felt was Stoppard’s genius, to be able to please and entertain an audience, as well as stimulating their mind.)

As for insularity you write about on this blog, you’re right! Isn’t it strange? The television news, the magazines, the shinsho — they are all full of these issues that the theatre is not exploring. I think chelfitsch has addressed/is addressing some Lost Generation issues but it is a shame to see great, talented gekidan like Ikiume and Sample focussing on Absurdist drama. They do it well but it kind of feels like it’s been done before. But it pleases their audience who have come to expect a certain style; they are ‘fans’.

It’s still something I’m looking into, but, unlike the current generation of British playwrights who were influenced by people like David Hare and Howard Brenton, the Japanese dramatists who have emerged in the last twenty years perhaps show more signs of German/European theatre. Interestingly, this year we have seen a large number of German plays performed in Tokyo. You draw an interesting parallel with the generation who got the Japanese theatre scene started thirty, forty years ago — and how political they were! (Of course, this was also the time of the anpo, the student riots, the Japanese Red Army etc.) I wonder how much influence the 1960s avant-garde directors and writers have really had?

LikeLike

Thanks for your detailed and interesting response. You seem especially interested in socially aware, political theatre, which seems to me to be unfortunately a particular weakness of the current Tokyo stage. It is difficult to compare it, moreover, with the London stage as the latter is perhaps at least one of the best theatre capitals in the world. The trouble with Tokyo stage seems to be that theatre people and audiences are sort of isolated from each other and there is not that much mutual fermentation among them. Each genre, each generation tends to be busy preserving their own tiny tradition and skill (typical in older Shingeki companies, perhaps except Bungaku-za), and is happily ignorant of others.

In London, there are a large number of people who want to see everything form fringes to NT to musicals. The practitioners also work in very varied venues; well-known stars could be found working in a tiny venue for a pittance. The result is the happy mixture of young and old, of established professionals and new talents producing exiting theatre scene, of which you must be much more aware than I do.

Regarding political theatre in Tokyo, the inertia on stage only reflects the conservatism of the theatre-going public: they are not interested in politics. But, as you must be aware, there are exceptions as some recent productions which took up Japano-Korean relations etc like Hirata Oriza. But, as my interest lies in western plays performed in Tokyo and London, I don’t know very much about them.

I may sound as if I despaired of Japanese stage, but I am not. The particular strength of Japanese stage, or Japanese culture in general, is the fact extremely varied performing traditions exist simultaneously in contemporary Japan. In that sense, the “clique-ishness” of Japanese theatre troupes works in favour of its variety. In a small country like Japan, you have Noh, Kabuki, and Bunraku, the three major traditions which are good enough to influence theatre practitioners around the world. Then you have peculiar offshoot of Kabuki (I think) like Takarazuka and Shinkokugeki. There are also the provincial folk theatre performed in seasonal festivities and Taishu-engeki touring small venues. All these on top of the regular staples which you see in major theatres.

Well I wrote too much for a comment. Thanks for reading my idle talk. Yoshi

LikeLike

Thanks again for your comments, Yoshi. It is very enlightening to hear the ideas of someone well-versed in both British and Japanese contemporary theatre. I think you are right about comparing London and Tokyo theatre; it is unfair considering the difference in scale.

Thank you.

Will

LikeLike