words

Direction: Takuya Murakawa [Japan]

November 8 (Thu) – November 11 (Sun), 2012

Adorno famously said that after Auschwitz, to write poetry was barbaric. A now hackneyed quote wrenched aphoristically out of context, indeed, but nonetheless this is much like the dilemma facing Japanese artists today. How do you turn the Tohoku and Fukushima catastrophes into art? Is it possible? Or is it offensive to even try?

One approach is verbatim theatre.

Following his acclaimed 2011 docu-theatre project Zeitgeber, which looked at the quiet dignity in the occupation of a care-worker, film-maker and theatre director Takuya Murakawa returned to Festival/Tokyo to present a brand new piece, the result of voluntary field work and a road trip in Tohoku following the March 11th catastrophe.

Introduced by Murakawa himself in his usual casual style, words (Kotoba) at the Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, Theatre East was a meditation on an “amateur” attempt to express an experience of the post-disaster world.

Takuya Murakawa

Murakawa, in his trademark baseball cap, first explained that we were about to witness the performance and asked us to note the microphones set up in front of us and hanging above us. These would be turned on at certain times.

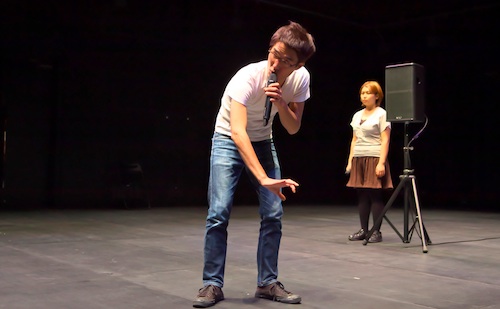

He then handed things over to the “cast”: two speakers, a man and woman, who narrated without drama their experiences, observations and stories of travelling in Tohoku and volunteering in the disaster zones.

Image: © Tsukasa Aoki

For the next ninety minutes on a stage devoid of anything except two chairs and two speakers they took it in turns to talk: it was simple, with no “dramatization” or attempt at reconstruction of the trip — but this very simplicity then took on a resonance, a poetical sound.

The two speakers did not speak to each other. Instead their exchanges were polite alternations: “words” ranging from the harrowing (finding bones) to the banal (snippets of a pop song); from stories and snatches of dialogue of meeting locals to finding rubble in a toilet when desperate to have a shit, or seeing a firework display in Rikuzentakata.

It would veer from the comic to the chilling, but it was always straightforward. Only the man occasionally almost seemed to “act out” his experiences. He spoke in a slang, while the girl was more reserved and formal in her Japanese.

Image: © Tsukasa Aoki

The microphones facing the audience and over our heads would be turned on when the two speakers paused and the audience was lit up. As Murakawa had explained, this was the moment when we were invited to speak and contribute — perhaps with our own experiences or thoughts on what had been said. No one did. The microphones (and the silence) merely reverberated, alone; a challenge, a condemnation? The echo embarrassed us — every shift, every cough was picked up and resonated back to us all, like a sound chamber confessional. There is a possible play on shindou at work here; depending on the way you write it this could be “vibration” or “tremor”. Thus sound and tremors are related, though silence is necessary not anechoic — something will bounce back and respond. And yet we are impotent, mutes who can only watch what is put on a stage for us.

Following a rather unsuccessful and under-used photo slideshow that slightly clumsily appeared halfway through, in the latter part of the performance a signer, who had previously been standing at the side and (in a relay with a colleague) providing sign language interpretation of the two speakers’ accounts, actually came on to centre stage. We then watched her, learning the gestures and how the words translated visually.

The ninety minutes finished with the girl warning of an “earthquake” seemingly happening right now. As the lights went down, we could see the signer fading into the dark, a provocation to our linguistic impairment.

Image: © Tsukasa Aoki

There was also an unintended double effect in watching the performance as a non-native Japanese speaker, meaning I was yet a further step away from the “words” and being able to understand them, to share in them — and to contribute my own.

And this is the current double bind: the Japanese (or, everyone residing in Japan) are all participants (toujisha) in the tragedy of Tohoku — and yet, we also are not. Like the characters in Jelinek’s Rechnitz: Das Würgeengel, we are simultaneously, ambiguously reporters, observers, participants — sharing the experience of the victims in part but also detached from the real victims. Distant, and due to this, potentially complicit in a obscure crime of non-participation, an impossible empathy.