In the theatre building, imaginary experience and real life are too strongly differentiated; the fine line that separates them is frozen solid. The performance onstage is a reenactment of reality reproduced by stand-ins. It is a safe form of imagination that will not invade the audience’s everyday reality.

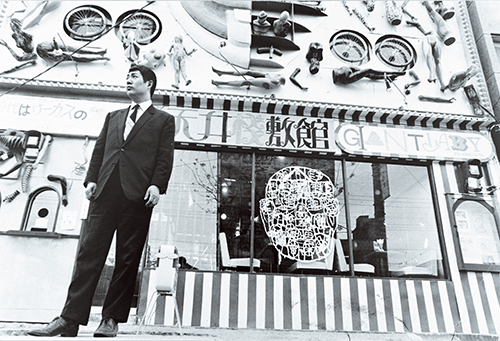

Shūji Terayama

Occupy Koenji. Over two nights in the Seventies, the streets of west Tokyo were taken over by a swarm of deviant actors, followed around by audiences amused, bemused and confused in no doubt equal measure.

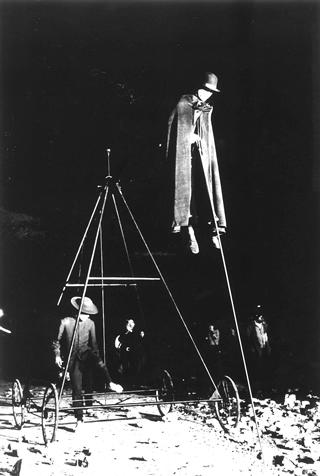

The thirty-hour performance was “an artistic assault on many fronts in Tokyo’s Suginami Ward” over two nights in April 1975. Coming off the back of the film Death in the Country, it was in many ways the culmination of the high period of experimental work by Shūji Terayama’s troupe Tenjō Sajiki, and the final full-scale outdoor theatre piece they did in the public sphere. The work of their later phase, the last eight years until Terayama’s premature death in 1983, were typically in more conventional spaces, or the time was spent touring in Europe and elsewhere. Knock is arguably the most definitive example of Terayama’s shigaigeki — often translated as “town theatre” or “streets theatre”.

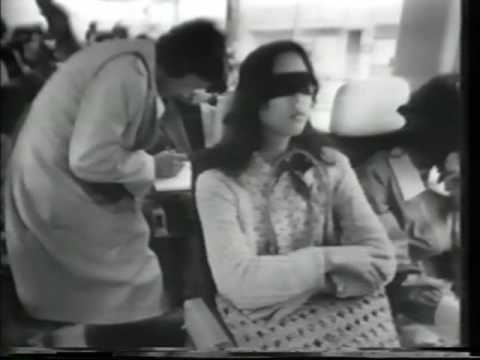

Knock was also an experiment in authorship and text. The roughly eighteen parts were authored by numerous people, including Terayama and Rio Kishida, his frequent script collaborator. Dialogue was numbered and characters were not defined. Needless to say, a lot of freedom and improvisation came into play in the scenes. This extended to the audience too, who, blindfolded and transported around by bus, were given maps and allowed to wander from site (sight) to site over the course of the hours. It was impossible to witness all the spectacles and happenings — and that was not the point. The intention was to make audiences explore the streets, heading into bathhouses, parks, “operating rooms” or, in some (unfortunate? fortunate?) cases, volunteering to be boxed up in crates and transported around Koenji (“human boxing”, as it was called).

Terayama once told a German journalist that his drama was neither a happening, nor ritualistic or symbolic — but that it was also all of these at the same time. Knock was an encounter with strangers and fellow complicit on-lookers (yajiuma) — local residents, intruding performers (if you could tell them apart), and fellow spectators. Terayama felt theatre had grown decadent and he wanted to shake it up. He did this by creating a “letter drama”, mailing snatches of “foreign” texts to residents. Fifty people were mailed with official-seeming correspondence, telling them to come to a certain place at a certain time to collect an unspecified lost item. Needless to say, this was on thin legal ice and the police were in fact called.

One of the most famed sections (and the most preserved) is the episode in the public bathhouse. This was theatre in disguise; the actors paid, undressed and entered the communal tub like ordinary customers. The non sequitur dialogue (“It’s man’s actions that create history, not his feelings.”) that had been prepared was Dadaist, arbitrary. The actors could perform what was scripted as they wished, as the mood took them from moment to moment.

Those who carp that local authorities in Japan (and elsewhere) and others make life difficult for putting on performances outdoors or in the streets can take some comfort in knowing that this is not new. Knock was also controversial, being greeted with minor scandal in local papers for the disturbance it caused in west Tokyo (“Troublemaking theatre is rampant,” scorned one newspaper).

The legacy of Knock is currently being commemorated at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art in central Tokyo.

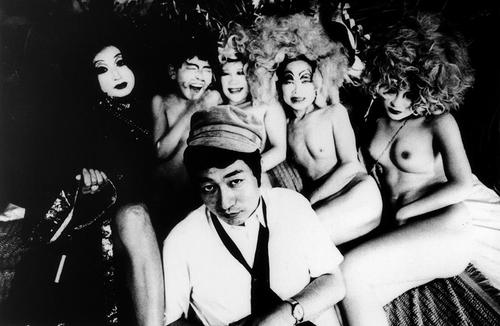

The Shūji Terayama “Knock” Exhibition runs until October 27th and features videos, photos, writings, posters and other resources from Tenjō Sajiki’s productions. Despite the exhibition title, in fact only one section introduces Knock — the rest focuses on Tenjō Sajiki’s anarchic world as a whole and, while serious fans may not learn much they did not already know, it is nevertheless a good portal for the uninitiated to sample the carnivalesque Terayama landscape.

Watarium is one of the most innovative art museums in Tokyo in its use of space, frequently surprising visitors by taking them onto the roof of the building or into small cubbyholes. It is an appropriate venue for such an exhibition about Knock, given that past projects have also “taken over the neighborhood” as Terayama sought to do. The recent exhibition of fellow social renegade JR’s art saw the locale transformed with giant portraits of the faces of people from tsunami-hit northeast Japan painted onto the entire outside facade of the museum. (They are still there.) Talk about an original billboard ad for the show!

Etsuko Watari, the curator of the museum, has said in an interview in Art Space Tokyo that “to be more radical, we go outdoors.” For an exhibition of French artist’s Fabrice Hybert’s work, the sidewalk from Gaienmae Station was turned into a vegetable garden, leading up to the museum. Likewise, a 2007 exhibition of the work of Barry McGee saw the clean Gaienmae district transformed into a graffiti pleasure zone, with stickers and tags adorning vending machines, streets signs and more.

Terayama is actually undergoing a major renaissance right now. A starry production of his late play Lemming was recently staged at the Parco Theatre, and his other oeuvre is frequently revived on the fringe. Poster Hari’s Gallery in Shibuya regularly holds exhibitions of Tenjō Sajiki posters, plus we have seen a wealth of books and “mook” (booklets) published emphasizing the vibrant, photogenic world of Tenjō Sajiki. His films have been re-released on Blu-ray and his poetry, essays and other writings are now available in attractive new paperback editions.

But we should remember that Terayama’s reception in his lifetime was more mixed. Although he was famous enough to get productions on at the new theatre that opened at the Shibuya Parco and tour his work around the world, his personal reputation took a dive when he was arrested for prowling streets at night and allegedly peeping into homes. Although he had supporters, his poetry was actually more acclaimed by the Japanese literary world than his more scatological drama.

Although his troupe were invited to the European and American trendy cultural circuits, some audiences and critics were left bewildered. One New York critic reacted to La Marie-Vision that “it appears to be an intriguing environment in need of a play… Curiously, it is the surface of the show — the costumes, make-up, lights, props and that live scenery — that is glittering and imaginative. It is the interior that is lacking in insight and resonance.” German critics compared Terayama’s work, not favorably, to Hitler, while another American reviewer discarded Instructions to Servants as “nothing more than pornography decorated with pretensions.”

David G Goodman, the scholar who more than any other worked to introduce angura to the west during its peak in the Seventies, overtly preferred the work of more politically radical artists like Jūrō Kara and Makoto Satoh (the older and more literary Terayama was apolitical), and rarely mentioned, let alone promoted, the output of Tenjō Sajiki as an important element of the scene since it was, in his eyes, a mere facsimile of the European avant-garde.

But dying young is a guaranteed way to ensure a legacy. Terayama’s reputation has been cemented in the years after his early death, not least by the opening of the Terayama Shūji Memorial Museum in 1997 in Aomori, the northern Honshu prefecture of his birth — but which he left long behind to pursue a bohemian career in Tokyo and around the globe.

It helped that after his mother passed away a few years after him, control of his estate grew less stringent and snobby, allowing translations and books long on hold to go to press. Previously known in the west mostly only for his film output, in recent years we have seen a film retrospective at the Tate Modern in London, but also major academic book-length studies by Carol Fisher Sorgenfrei and Steven C Ridgely that emphasize his theatrical work and status as a countercultural impresario.

In the current climate of Japan’s theatre-building boom that is always seeking to create simplistic “black boxes” to sate government desires for local “cultural activities” baubles, many lessons can be learnt from the frenetic, anarchic and arbitrary exploitation of the public domain that Tenjō Sajiki attempted, perhaps most of all in Knock.

The influence of Terayama can be felt today in artists such as Akira Takayama (Port B), whose own brand of “touring” theatre also makes audiences move around local areas and explore new territories, as much as possibly by themselves. Fresh from success at the recent Wiener Festwochen, Takayama has in the past created site-specific outdoor theatre projects in Sugamo, Shimbashi, Ikebukuro and even on a Hato Bus (an echo of Knock) that toured Tokyo. His preference for using man-on-the-street-style video interviews in his projects can also be traced back to Terayama.

The rules and regulations that “protect” the public domain are tougher now, as impromptu street artists and musicians have found out to their frustration in Akihabara and Yoyogi. It would be much harder, perhaps almost impossible today to create a theatre experience like Knock. However, times have changed and we are anyway jaded by work that seeks too obviously to be provocative or “guerilla”. The actions of “controversial” art units like Chim Pom seem more cynical and manufactured than genuinely challenging. At best, they are merely naive.

Anyone waiting for another Terayama to arrive with a messianic caravan of theatrical revolution will ultimately be joining Estragon and Vladimir. It is far better to enjoy the heritage he left behind and look to the future.

Further Reading in English

Experimental Arts in Postwar Japan: Moments of Encounter, Engagement, and Imagined Return

Miryam Sas

Harvard East Asia Monographs (2011)

Japanese Counterculture: The Antiestablishment Art of Terayama Shūji

Steven C. Ridgely

University of Minnesota Press (2010)

Shades of Darkness: Kurogo in the Theater of Terayama Shūji

Yukihide Endo

University of California Press (2006)

Theorizing the Angura Space: avant-garde performance and politics in Japan, 1960-2000

Peter Eckersall

Brill (2006)

Unspeakable Acts: The Avant-garde Theatre of Terayama Shūji and Postwar Japan

Carol Fisher Sorgenfrei

University of Hawaii Press (2005)

Angura: Posters of the Japanese Avant-Garde

David G. Goodman

Princeton Architectural Press (1999)

Alternative Japanese Drama: Ten Plays

Edited by Robert T. Rolf and John K. Gillespie

University of Hawaii Press (1992)

Japanese Drama and Culture in the 1960’s: The Return of the Gods

Edited, translated, and with commentary by David G. Goodman

M.E. Sharpe (1988)

Modern Japanese Drama: An Anthology

Edited and translated by Ted T. Takaya

Columbia University Press (1979)

Damn, now that’s how you write a blog post. This one just keeps giving and giving. Chock full of good information and insight on a topic that is hard to find good information or insight on. Topped off with a mini bibliography even for those who want to explore even further. Reading your blog continues to be an education, thank you and please keep it up, there aren’t many doing what you do, and fewer who do it this well.

LikeLike

@Mark

Many thanks for your kind comment. I’m glad that the long wait since my last posting was worth the wait for some!

LikeLike

Our theater company is actually going to workshop a site specific piece inspired by “Knock” called “Vera and Linus” this summer ^_^ We also JUST finished a production of “La Marie-Vison” as well! Yay for Terayama love ❤ http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/72669046/the-disastrous-tale-of-vera-and-linus <- that is our Kickstarter if you are interested 😀

LikeLike

Great stuff! I’ve been doing some research on Terayama recently, so this is a great post to come across.

LikeLike

@Clark Parker

Many thanks. Your site is also a great resource.

LikeLike